For the pontiff, being humble is less a character trait than a calculated choice.

“Where’s my briefcase?” asked Pope Francis. The papal entourage had arrived at Fiumicino Airport in Rome for the pontiff’s first trip abroad. Jorge Mario Bergoglio had been pope for just four months and was now bound for Rio de Janeiro, where 3.5 million young people from 178 countries were waiting to greet him at World Youth Day in Brazil. And he could not find his briefcase.

“It’s been taken on board the plane,” an aide explained.

“But I want to carry it on,” said the pontiff.

“No need, it’s on already,” the assistant replied.

“You don’t understand,” said Francis. “Go to the plane. Get the bag. And bring it back here please.”

Members of the press, who were already waiting on the plane, soon saw from their windows that Pope Francis was moving purposefully through a crowd of functionaries to the aircraft, carrying a black briefcase in his left hand. This was a story: Popes had never before carried their own luggage.

During an impromptu press conference on the plane an hour and a half later, after the pope had talked at length about young people who had no jobs and who felt discarded by a society in which old people had long been treated as similarly disposable, one reporter asked what was in the briefcase. “The keys to the atomic bomb aren’t in it,” Francis joked. So what did it contain? “My razor, my breviary, my diary, a book to read—on St Therese of Lisieux to whom I am devoted. … I always take this bag when I travel. It’s normal. We have to get used to this being normal,” he added.

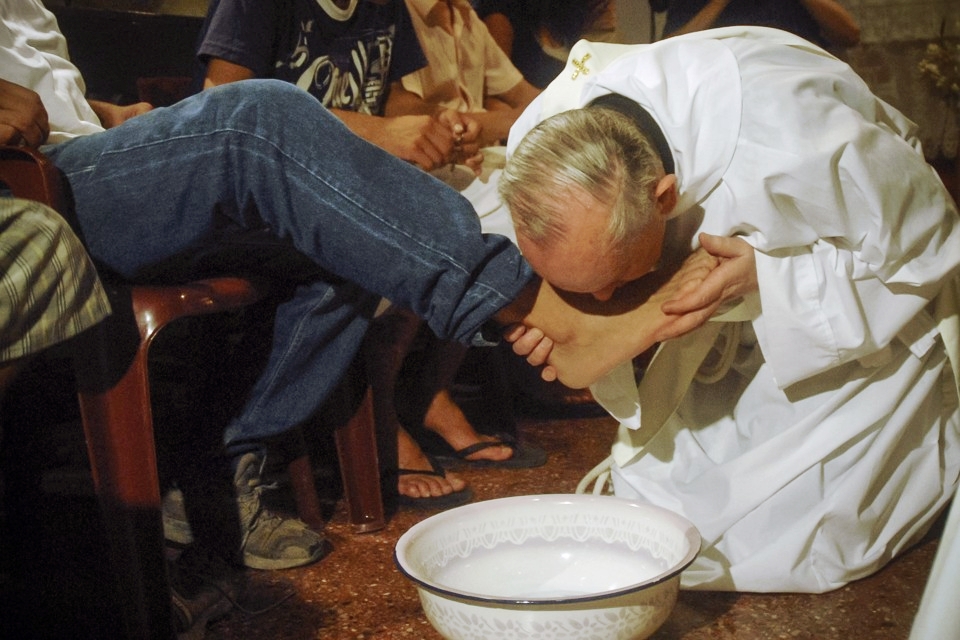

It’s a new normal: Francis has presented himself to the world as an icon of simplicity and humility, eschewing papal limousines and the grand Apostolic Palace, and instead being driven in a Ford Focus and living in the Vatican guesthouse. But being simple can be a complex business if you are the leader of one of the world’s largest religious denominations and also a head of state. And Francis’s life story shows that humility is not an innate quality of his, but a calculated religious, and sometimes political, choice.

* * *

Bergoglio’s progress through the ranks of the Society of Jesus, a religious order within the Catholic Church also known as the Jesuits, was remarkably speedy. In April 1973, at the age of just 36, he was made provincial superior, the head of all Jesuits in his home country of Argentina as well as neighboring Uruguay. But tensions produced bergogliano and anti-bergogliano factions that divided the province in two and ultimately resulted in the Jesuit headquarters in Rome exiling Bergoglio to Cordoba, Argentina’s second-largest city, some 400 miles from the capital.

There were two main, and intertwined, areas of conflict. One was religious, the other political. The religious division was over the Second Vatican Council, which shook the Catholic Church to its foundations between 1962 and 1965. Vatican II famously threw open the windows of a Church seeking greater interaction with, and influence on, secular society. As different sections of the Church began to explore how to apply the Council’s insights, a polarization occurred, and then deepened, between conservative and progressive factions within the Argentine Jesuits. The conservatives wanted to remain focused on their inner religious life and continue in their traditional social role of educating the next generation of the nation’s rich elite. The progressives wanted a more outward-facing spirituality and a shift to working with the uneducated poor in the shantytowns. The political division centered on Liberation Theology, a new approach to Catholic teaching that declared a need to liberate the poor not just spiritually but also from unjust economic, political, or social conditions. Progressives were enthused. Conservatives rejected the theology as Marxist, and a way of allowing communism into Latin America through the back door.

Courtesy : The Atlantic